You’ve probably never heard of Santiago Swallow, Expert on Inauthentic Identity, Author of “Self'”.

You’ve probably never heard of Santiago Swallow, Expert on Inauthentic Identity, Author of “Self'”.

I had not heard of him either until last week when I came across an article in Quartz titled “How to become internet famous for $68” by Kevin Ashton, known for inventing the term “The Internet of Things“.

I am presuming that Kevin is real, but I have no way of proving this…

In summary, Kevin created Santiago, gave him a Wikipedia entry, an official looking website, and bought him thousands of Twitter followers to make him look real.

He even faked the “verified” logo on his Twitter bio to appear legitimate.

The @SantiagoSwallow episode shows us that now you have to do your fact checking on social media as well as for all other forms of media – you just can’t believe everything you read on social media…

What the article highlighted so well is what those who work in the industry have known all along – you can game pretty much anything – even life.

People have been gaming things long before the internet – we call them “con artists” and they exist today.

The article also reminded me of the adage “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog“, first coined as the caption of a cartoon by Peter Steiner published by The New Yorker on July 5, 1993.

While it is not yet a crime to buy twitter followers or Facebook likes, those people who want to appear more popular, and hence (in their own eyes at least) more valuable to prospective employers, clients or brands, are engaging in these deceitful practices, because they believe they can get away with it.

Back in February 2013, the Wall Street Journal published an expose titled

“The Mystery of the Book Sales Spike – How Are Some Authors Landing On Best-Seller Lists? They’re Buying Their Way”

What the WSJ investigation proved was that even an age old process such as the best seller list can be gamed – in an offline way just by buying lots of books just before it goes on sale.

In a follow up to the WSJ article, Soren Kaplan, the author of the book “Leapfrogging” who was quoted in the article, came clean in his own words and admitted that yes, he had manipulated the sales to claim bestseller status.

So we can probably assume the “bestseller scam” has been going on for years, and now people are turning to social media to buy fame – just as Kevin’s article proved.

When we talk about social media popularity and fame, the discussion inevitably turns to social media influence.

As Kred was mentioned in Kevin’s article, and while I was CEO, I thought it appropriate to respond directly to what Kevin found in his experiment.

Kred is the only influencer platform that is completely transparent. Kred published their rules to show exactly how it scores (no-one else does this), and also shown on every Kred profile is every single interaction. In short – I could see @SantiagoSwallow gaming the system.

On other platforms, you can see that Santiago Swallow has a score, but unlike Kred, you have no idea how that score has been developed.

While Kevin asserts that his creation of @SantiagoSwallow fooled sites such as Kred into believing he was influential, Kred can be used to weed out the fakes as well.

A quick glance at the Kred profile of @SantiagoSwallow shows quite clearly that there has been a massive influx of flowers – from zero to over 74,000 almost overnight.

To even an un-trained eye, something does not look quite right here, and would be worthy of further investigation.

Because Kred publishes every single public interaction on each Kred profile as an activity statement, with a few more clicks, you can start to see very easily that this whole profile is one big con. Click the image below to see the evidence – look at the large influx of followers in batches. You can see this for yourself at kred.com/santiagoswallow

The other giveaway that Santiago is not real can be detected by looking at his community scores.

While his global Kred influence score is a reasonable 754, when you zero on his community scores (as any well-educated brand manager would do to see where this person has influence), you see that he has very low influence in his top listed communities.

In the examples below, in Santiago’s top 3 communities, he has woeful community scores of just 150/1 for Reporters, 125/1 for Marketing and a “why bother” score of just 54/1 for publishing. In under 30 seconds on Kred, I knew Santiago was a fake.

What this whole experiment has shown is that yes, while you may think you have fooled someone by having lots of followers, or likes, or an apparently large Kred score, you’re only fooling yourself.

Santiago’s low outreach score of just 4 is also a giveaway that he has no real influence – he doesn’t really engage with his community.

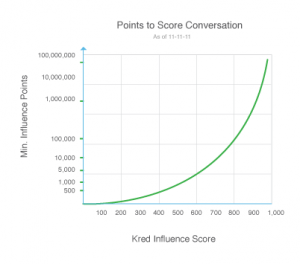

On closer inspection of his Kred profile, Santiago has 75,000 raw Kred points, and as can be seen from this double-logarithmic chart from our rules page, it is increasingly harder to increase your global score.

Those who show signs of real global influence have a Kred score above the 850 mark, where you need hundreds of thousands of raw points (vertical axis), and Santiago cannot do that by just buying more followers.

He would need to have real influence, by interacting with his community, and his community interacting with him in an authentic and sustained way.

As the former CEO of Kred I saw first-hand people telling me how influential they are, only to then see the same person unleashing hundreds of fake twitter profiles, who each have exactly 4 followers, using software to automate retweets by these profiles of the same message tens of thousands of times to try and increase their Kred score.

We know we cannot stop people gaming our own, or any other system. Instead, it is important to focus on transparency and education to allow the early detection of “twitter fakes” when working with clients so they don’t have to waste their time on those who try and artificially increase their social footprint.

Sadly, even some that appear on top “influencer” lists (and best-seller lists) openly boost their profile and score through well-known techniques such as the ones detailed above. It is an open secret in the industry.

Those of us with integrity ensure that brands don’t use these people in their influencer and advocacy programs, however I cannot get to every brand manager and agency person in the world to educate them on the pitfalls of picking the person with the “highest score”.

Experiments such as the one undertaken by Kevin highlight the dangers of relying on influence scores on their own.

Last year I wrote an article titled “Employers need to understand the dangers of influence score myopia” in response to news that Salesforce was hiring someone who as a minimum had to have a Klout score of 35 or higher.

These scores are meaningless unless you know WHERE the person has influence – not just the score. As has been proven above, one look at Santiago’s Kred profile shows he has no real influence at all.

The challenge for the influencer industry is how do you educate people who are in a hurry to find “influencers” that it is not always about the person with the highest score. As mentioned above, we decided to be transparent from day one, and have seem none of our competitors follow our lead.

So next time you see someone quote a high influencer score on their profile, CV or pitch response, pop over to Kred and have a look in more detail – it might just be Kevin doing another experiment, or someone trying to improve their social capital in an artificial way.

Just a few moments on Kred could save you and your company from another “Santiago Swallow” moment.